The MANSFIELD, flagship of Commander Destroyer Squadron NINE, was one of six (6) destroyers selected for the reconnaissance in force of Inchon Harbor on 13 and 14 September 1950. The ship had been employed in blockade and shore bombardment of the enemy coast of Korea from 25 June until 8 September 1950. The ship was assigned to Task Force 90 (Fire Support Group) on 12 September, following three (3) busy days in port for replenishment and indoctrination of the planned assault.

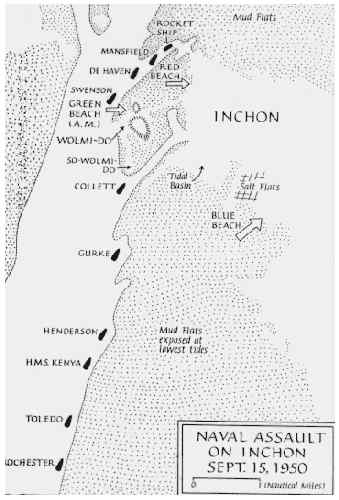

Departure and speed of the task group were set to bring the force off the approaches to Inchon, Korea on the morning of the 13th of September. The first sign of enemy activity came about 1100I when mines ere sighted off the port bow at a distance of about 3,000 yards. The DEHAVEN and SWENSON, immediately astern, joined with the MANSFIELD in taking those under fire, and exploded one. Others were destroyed by the USS SOUTHERLAND, while the five remaining destroyers proceeded on toward Inchon.

The MANSFIELD continued leading the destroyer reconnaissance force up Flying Fish Channel, past Wolmi-Do Island into Inchon Harbor, arriving as scheduled. At 1248I anchored, and 1302I commenced firing upon selected targets, principally gun emplacements along the sea wall, plus some emplacements on the hills of the city. 154 rounds of 5" AAC were expended in pin-point shooting at the targets. A total of 18 were directly hit. At 1320I observed shell fire being received by destroyers in the second section anchored south of Wolmi-Do (USS COLLETT and USS GURKE). At 1400I weighed anchor as scheduled and followed destroyer unit out of harbor. Counter battery fire was received around this ship beginning about 1411I during retirement at full power while passing the shore batteries. When south of Wolmi-Do at a range of 3,500 yards the coast defense batteries there were taken under fire by our full battery of six (6) 5 inch guns and eight (8) 40MM. The 5" salvos landed close to the western gun emplacements and some shots may have hit. The dust and smoke from this fire drifted eastward across the several batteries visible and obscured their vision for a period of one (1) or two (2) minutes, during which reduced counter battery fire was received.

The relative bearing of the targets now drew rapidly aft and only 5" mount No.3 could bear on the emplacements. Splashes were again observed falling around the ship. Emergency full speed was called for at 1415I and obtained from the engine rooms, rapidly reaching 33-1/2 knots.

The bearing of the enemy positions was now such that the director optical system was obscured by the mast. The firing circuit cam cut out one gun of mount No.3 due to low elevation angle. No fall of shot was seen on Wolmi-Do at this time except from our 40MM battery. The commanding officer ordered indirect fire against the enemy, rapid fire from mount No.3. Enemy shells continued to fall on all sides of the ship, one clearly seen by the commanding officer and several others to pass between the stacks and land about 15 yards to starboard. The damage control officer in the engine room reported hearing 3 shell explosions close aboard during this retirement. Fifty (50) rounds of 5" AAC were expended at indirect fire with conclusive results in the appearance of many ground bursts on Wolmi-Do. The enemy fire again slackened. When the range to the island reached about 12,000 yards, the enemy shells began to fall short of the ship. At 1423I speed was slowed. The British cruiser KENYA was now observed firing her 6" guns over our ship providing covering fire against Wolmi-Do. Ammunition expenditure for the ship in this reconnaissance totalled 170 5" AAC and 420 40MM. No Casualties were suffered by this ship, although the destroyers present were hit with about ten (1) wounded and one (1) killed.

[Left: This picture was taken during the assault on Wolmi-Do at Inchon September 13, 1950. Left to Right: Ens. William Barnes (back view) on the sound powered telephone. LTjg. D. J. Winnie, First Lieutenant and LTjg (MCR) R. H. Lee, Medical Doctor (ComDesRon9 staff).]

[Left: This picture was taken during the assault on Wolmi-Do at Inchon September 13, 1950. Left to Right: Ens. William Barnes (back view) on the sound powered telephone. LTjg. D. J. Winnie, First Lieutenant and LTjg (MCR) R. H. Lee, Medical Doctor (ComDesRon9 staff).]

The second reconnaissance in force, at 1300I on 14 September, was carried out on schedule similar to the previous day, except that a more effective air strike preceded our entry. The MANSFIELD followed the HENDERSON to a point 8,000 yards from the enemy batteries on Wolmi-Do, where the HENDERSON took station for counter battery fire. The MANSFIELD then proceeded up channel in the lead of the destroyer unit passing Wolmi-Do without incident. She took station (remaining underway) and at 1256I opened fire upon more gun emplacements on the beach and in the hills of the city. Retirement was made at 1415I passing Wolmi-Do, again without return fire. The silence of the coast defense guns on Wolmi-Do on this date is believed due to one (1) location of the emplacements by the destroyers on the 13th: two (2) air strikes approaching down the throat of the enemy guns; and three (3) pin-point, point-blank fire of the destroyers immediately following the air strike. The MANSFIELD expended a total of 154 rounds of 5" AAC and 1140 rounds of 40MM shells, on this reconnaissance fire.

The next approach to the target area was made early on the 15th, the MANSFIELD again leading the entire invasion fleet. Anchor was dropped at 0426I during darkness in the innermost berth in the harbor and at 0554I fire was opened on visually selected targets along the Inchon waterfront, in accordance with the schedule for LOVE hour of D-Day.

At 0628I fire was ceased and at 0630I the landing of troops commenced on time.

At 0709I the island of Wolmi-Do was reported secure.

At 0801I the MANSFIELD received her first call fire mission from the Shore Fire Control Party; an enemy field piece located near the main railroad station in Inchon. It was destroyed with six (6) rounds of 5" AAC. During the remainder of the day a total of seven (7) call fire missions were supplied the troops ashore. typical of these was call fire for a gun emplacement over a hill, requiring a reduced charge, on round was sent to the target and a spot of "right 50, add 50" was received. A second round was fired with this correction. The spotter then replied "target destroyed, end of mission." Time for knocking out this Red Gun was five (5) minutes.

Also throughout the day until HOW Hour visible targets were selected and fired upon. A total of 596 rounds of 5" AAC and 1170 rounds of 40MM shells were expended in this manner on carefully selected covered gun emplacements, revetments, trenches and bunkers.

After 1730I when the main landing was made, the ship fired only at hill top emplacements suspected of opposing the landing force. At 1953I the ship's company secured from General Quarters, having been at battle stations since 0340I.

On the 16th the ship remained at anchor, providing gunfire support for our advancing troops.

During the night of the 16th and 17th the ship was assigned illumination fire missions. Fifty (50) star shells were fired hourly throughout the night, lighting up a road junction near the Third Battalion of the Fifth Marines, which unit we were supporting.

The enemy aircraft which attacked the USS ROCHESTER and HMS JAMAICA about 0600I this date did not approach the MANSFIELD.

On the 17th, three (3) fire missions against retreating enemy troops were assigned. Thirty-two (32) rounds AAC and four (4) rounds VT were expended on call.

At 1731I on the 17th the MANSFIELD got underway for replenishment, proceeding to rear anchorage for re-fueling and re-arming.

On the 18th this ship, with ComDesRon 9 embarked, was assigned the duty of meeting the only active battleship of the fleet, (USS MISSOURI) and escorting her up Flying Fish Channel to the Inchon Anchorage. After observing HMS MOUNTS BAY drop a depth charge pattern on a reported submarine contact, the MISSOURI anchored up the channel awaiting flood tide. At about 1130I on the 19th the MANSFIELD led the MISSOURI to her gunfire support anchorage, and then moored alongside her for obtaining mail, freight, and passengers for delivery to ships of the gunfire support group present.

On the 20th and 21st the MANSFIELD occupied air defense station in the anchorage, near Yodolmi Do Island.

On the 23rd the MANSFIELD, along with the SWENSON and DEHAVEN, were detached from Task Force 90 and returned to Task Force 95. Those ships under command of Commander Destroyer Squadron NINE arrived at Sasebo, Japan for replenishment at 1700I on 24th of September.

(AP)--The landing at Inchon, in a large part, is the story of six brave little ships and a wonderful blunder. The North Koreans made the blunder. The little ships, the big ones, the planes and finally a Marine assault force capitalized on it. A chain of events started by these six ships led directly to the victory at Inchon.

In the entrance of Inchon Harbor, and commanding approaches to it, is the island of Wolmi. It is a wooded island shaped like an oyster shell. From the beaches, the ground rises 300 feet to a rounded top. A stone causeway connects the island to the Inchon waterfront. Wolmi was the key to the entire operation. Before the main attack could begin on Inchon, Wolmi has to be taken. In an order issued before the battle, Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, commander of Task Force 90, said: "This mission (Wolmi) must be successfully completed at any cost. Failure will seriously jeopardize or even prevent the major amphibious assault on Inchon, therefore, press the assault with the utmost vigor despite loss or difficulty."

Big questions loomed--what did the North Koreans have on Wolmi to defend it? How many guns? How big? Where? Six brave little ships--six destroyers--were sent in to find out.

Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble, commander of Joint Task Force 7, ordered a "reconnaissance in force." The mission frankly was to draw fire from Wolmi--the more the better. A destroyers' armor is three-eights of an inch thick. Practically anything stronger than a slingshot will pierce it.

On the morning of September 13, "D-Day minus two," the six brave little ships, moving in column, and slowly, sailed into the narrowing channel leading pass Wolmi to Inchon. On anchored off the southern face of the Island. Three passed through the neck of the channel to the other side. Two remained in the channel. None was more than a mile from the beaches and some were 1,000 yards--two thirds of a mile.

They were "sitting ducks". That's what they were meant to be, juicy targets for concealed guns on the shore.

From all over the elbow of the channel further down, thousands of binoculars were trained on them from American and British cruisers. The silence was like a blanket. It was a brilliant sunny day and you could see even without binoculars. Suddenly there was a single sharp white flash. Seconds later the muffled crack of the gun came back. "The 730 reports she spotted a battery moving on the beach," a report to the bridge of the flag ship said. A few more tense, breathless, incredible seconds of waiting passed. Still silence. Wolmi Island looked like a picnickers paradise, green-wooded and serene.

Then the North Koreans made a fateful and wonderful blunder. Suddenly a necklace of gun flashes sparkled around the waist of the island. The flashes were reddish gold and they came so fast that soon the entire slope was sparkling with pinpoints of fire. The destroyers were quick to answer. Lightening flashes leaped from their guns. They hit back, shell for shell, firing faster and faster until the whole channel was a tunnel of running thunder. The pace increased, on Wolmi, still more gun positions opened up. The red necklace spread and widened. They were hitting destroyers now. They could hardly miss at that range. Then a report came down to the bridge and you blood ran cold "It looks as though the 783 is dead in the water, sir." Admiral Struble's answer was quiet and the words were taut. "Make sure, and see what we have to do to get her out of there."

The duel went on for an hour. It was a slugging match, toe to toe, and nobody quit or backed away. Six brave little ships sat there and shot it out with the dug in enemy gun crews on Wolmi Island. Three of the six were hit, one seriously, but not so serious that she could not come out under her own steam. An officer died. There were other casualties.

The destroyers came out proudly and without haste, still firing flat trajectory fire at close range and then at higher arcs as the distance increased. The mission was accomplished successfully, the Navy will say --Gloriously is a better word.

If the guns on Wolmi Island had never been discovered--it the North Koreans had not blundered into exposing their armament, it is hard to say what might have happened to the transports and the little landing craft when they came in for the assault two days later. On "D-Day". At best, the casualties would have been enormous--for Wolmi Island is studded, or was, studded with guns--at worst, the invasion could have stalled right there at the first objective.

Six brave little ships exposed themselves to fire. The bigger guns and hordes of planes knocked it out before the Marines ever appeared. Six brave little ships: The MANSFIELD, 728--The DeHaven, 727--the Collett, 730--the Lyman K. Swenson, 729--the Gurke, 783-- --and the Henderson, the 785.

--END--

This article by Capt. Headland mentions two DD's that were in the same DES DIV, Gurke & Henderson, as was our ship the McKean DD 784.

We were shore bombarding at Samchok on the east coast of Korea. We were with the "Big Mo", Helena and another destroyer. We joined them (I thought), later that day, but after reading where we were, we must have arrived there the next day as we were 450-500 miles away.

Samchok is east of Inchon on the east coast of Korea. We saw all the devastation that Inchon suffered. Some crew members went in our ship's 38 foot whale boat and took pictures and surveyed the area. A previous article written by a crew member of the USS Henderson described what they did. The author was a firecontrol man and was in the MK 37 director doing the spotting of targets and directing fire.

It is great to find this information after so many years. The Navy had it easy compared to the Marines and Army. In spite of being on ships many sailors were killed by mines and some by shore shell fire. Keep our servicemen and women in your prayers. - Richard Shaw [FT USS McKEAN DD-784]

By Captain Harvey Headland 35, U.S. Navy, Retired USNA Class of 1935.

By Captain Harvey Headland 35, U.S. Navy, Retired USNA Class of 1935.It was near the end of June 1950. Destroyer Squadron Nine, along with the light cruiser Juneau, was deployed in Japanese waters, while the major portion of the U.S. Seventh Fleet patrolled off Indo-China (later called Vietnam), where a combat situation was in progress between France and the local communist rebels.

Squadron Nine, Division One, looked forward to a flag-showing cruise at various Japanese ports. But on 25 June, just as Commodore Halle Allen and I were about to visit the local culture-pearl farm near Sasebo, news arrived of North Korean forces crossing the 38th parallel into South Korea.

We soon learned that the United Nations (U.N.) organization intended to counter this invasion with military forces. Hence, we also soon found our ships interdicting traffic routes on the coasts of Korea as well as conducting shore bombardment of industrial sites in North Korea. This action continued through July and August.

Then came news (secret) of plans for an amphibious landing by U.N. forces in the southern part of the peninsula near Pusan, as the North Koreans had overrun most of South Korea. However, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the U.N. forces in the area, and military governor of Japan, proposed a strategy that would create an ambush by deploying U.N. forces in the rear of the enemy.

His alternative plan was to enter Flying Fish Channel on the west coast of the Korean peninsula with an amphibious landing at Inchon, the port for the capital city of Seoul. The enemy could be cut off from its line of supply and forced to retreat. This deployment was chosen over the frontal attack first planned, and on 10 September, aerial bombing of the approaches to Inchon began.

The hazards of approaching and attacking Inchon are considerable, if not miserable. The tides there reach 30 feet, with resulting tidal currents of 5 knots. The tides determine the date and hour of entrance to the port. An amphibious invasion could be attempted only a few days a month.

Another hazard was the pyramidal island of Wolmi-do guarding the inner harbor. Its location gave it command over the sea approaches in every direction. It had to be neutralized before a landing could be done. Wolmi-do was called "the cork in the bottle" for this operation.

As part of the plan to locate enemy gun positions on Wolmi-do, the destroyers of Squadron Nine would be sent in first, to tempt the gunners on the island to disclose their positions. The destroyers were required to enter the harbor at flood tide, anchor at the short stay, and be ready for anything. Thus they acquired the name they have held ever since: "The Sitting Ducks."

On 13 September, the augmented Seventh Fleet navigated its route through the very limited waterway of Flying Fish Channel en route to Inchon-Seoul. In the lead was Destroyer Squadron Nine, composed of Mansfield (flag-Commander E. Harvey Headland), DeHaven (Commander Oscar B. Lundgren), Lyman K. Swenson (Commander Robert A. Schelling), Collett (Commander Robert A. Close), Gurke (Commander Frederick Radel), and Henderson (Commander William S. Stewart). The latter two were not regular members of Squadron Nine, but were added for this operation.

The six destroyers broke away from the other elements of the fleet and proceeded up the narrow confines of Flying Fish Channel that led to the port and planned landing beaches. They were in column, led by Mansfield. As the approach continued for about four hours, a Korean interpreter aboard Mansfield reported hearing a broadcast, warning the Wolmi-do defenders that we were coming. The next hazard encountered was the sighting of enemy mines, not yet submerged by the rising tide. Henderson was detached to destroy these while the remaining ships advanced up the channel. Now the 350-foot mount of Wolmi-do appeared dead ahead, and soon the vessels all reached their assigned position in the inner harbor and anchored, without any exchange of fire. It was an eerie silence in a combat situation. Collett and Gurke were the nearest to the fortified Wolmi-do, only some 700 yards away. With the hauling down of the flag hoist to execute the assigned mission, firing of the destroyers' 5-inch guns commenced. At first the shore batteries did not respond, but only for a few minutes. Then the shore batteries concentrated their fire on the ships closest: Collett, Gurke, and Swenson.

Collett was hit five times, with five men wounded and her firing computer damaged. She moved out of range. Gurke was hit three times and sustained two men injured. Swenson was not hit, but Lieutenant Junior Grade David H. Swenson "48 fell from a shell or fragment (See "The Pabst Blue Ribbon" p. 18).

Thus the "Sitting Ducks" accomplished their mission of causing the enemy to disclose their position and power. All this required less than an hour and, conscious of the now-falling tide, the destroyers began their retirement. Fortunately, none of the ships were damaged in its propulsion machinery.

As Mansfield, the first ship in and now the last one out of the inner harbor, passed close by the shore batteries, I cranked up flank speed. From the wing of the bridge, I actually saw shells flying over the ship. "Some kind of miracle," according to some accounts of the action.

Upon reflection, one can deduce the ship was passing under enemy guns close enough to be below their depression limits. This is exactly what happened on Mansfield, to my consternation. Naturally, I felt defenseless in the midst of battle. (My guns firing was cut off by depression limits to avoid blasting personnel nearby.) At this point neither the gunnery officer nor I recognized the cause. To cease firing would have been my last possible thought.

Not receiving any sensible response from the telephone talker, I went outside the pilot house and climbed above the bridge where the gunner director was located. By this time, the cause of our gun silence was understood. Then, to display some sort of counter battery, I ordered the 40mm antiaircraft guns to open up. These mounts were not restricted by depression cams, and with bright red tracers on all shells, a good display of offense was created, if not greatly destructive of enemy gun positions.

Thus we exited the inner harbor, last in the column, without any damage to ship or personnel. I have been thankful to God ever since.

Besides events like the unexpected cease-fire of the 5-inch guns while under attack, there were other events that Mansfield encountered not reported in all battle reports. One was the boat tour of General MacArthur in his barge, circling the destroyers following the silencing of the enemy guns. We made no attempt at honors, such as manning the rail in this battle scenario. Another was an attack by an enemy YAK propeller plane on the cruiser Rochester, when its missile hit the aircraft crane on the stern, exploding and injuring two personnel.

A second YAK plane strafed the Royal Navy cruiser Jamaica, killing one British seaman. This plane was shot down by Jamaica's antiaircraft guns and recovered by our allied forces nearby, still in near-perfect condition. We understood it was the first YAK recovered by our forces, becoming a valuable object for intelligence study.

With the enemy now driven from the beaches, the Marine landing from LSTs and other landing craft proceeded, placing thousands ashore at the next high tide the following day. For the destroyers of DesDiv 91 and its two sister ships, our "Sitting Duck" episode was finished. We went on to other duties, primarily shore bombardments, such as the siege of Wonsan on the east coast of the peninsula. Except for short periods of three months for stateside repairs, the destroyers remained in Korean waters for the three-year duration of the war. I, for one, had 22 months in Mansfield, and eventually became "Papa Duck" as senior CO.

In retrospect, this operation of placing destroyers as targets to tempt the enemy to disclose its positions was an audacious undertaking. Its success (at the sacrifice of Lieutenant (jg) Swenson and injuries to eight men) was a great credit to the U.S. Navy's aggressive spirit and courage.

[Harvey Headland, 35 began his career with a five-year tour in Quincy (CA). During WWII, he was CO Pope (DE) and DivCom in Buckley (DE). After shore duty at Mare Island, he was CO Mansfield (DD) for action in Korea, followed by duty in the MAAG program in Paris. More shore duty stateside, a tour as CO Ponchatoula (AO), and a second career in the academic world. He picked up two MBAs and began teaching for the University of Puget Sound in 1963. In 1968, he went overseas for 11 years with the University of Maryland, teaching at various U.S. military bases in the Far East and Europe, then returned to teaching in Tacoma, WA, returning in 1990.

Captain Headland's Deceased Shipmates listing.

1. The Captain sends the following message to the entire ship's company:

The MANSFIELD has successfully led the entire invasion force into the INCHON-SEOUL area, after leading two bold raids into th every center of the dangerous enemy harbor on the 13th and 14th. Many treacherous enemy gun positions around the beaches and hill tops were knocked out by our guns. Two or three of our sister ships were hit with casualties to personnel and equipment.

Our successful completion of this history-making operation without casualty is due to the maximum efforts of all departments of the ship, plus the favor of Lady Luck. To all hands a VERY WELL DONE and sincere congratulations for you great contribution to the invasion of the INCHON-SEOUL area of Korea. Keep up the good work against the Red enemy who are still active against us until peace is restored on our terms.

2. NAUTICAL TERMS OF THE DAY

FAST: secure

FATHOM: a unit of measurement, six feet.

(Signed)

P. W. Frazier, LCDR, USN,

Executive Officer.