Although it was not until August 1964 that destroyers in the Vietnam area first made headlines, when they were fired on by torpedo boats in the South China Sea, both destroyers and cruisers have been active in the Vietnam War since its very beginning.

As the conflict began to grow more serious and the United States offered more assistance to the Republic of Vietnam, the jobs assigned to cruisers and destroyers in the area began to grow--both in number and complexity--and more ships began to take part in the war. Today, ships of the U.S. Seventh Fleet Cruiser-Destroyer Group number more than 60, virtually all of them operating in the Vietnam Area.

Throughout the South China Sea and the Tonkin Gulf, cruisers and destroyers are known for their versatility. Because of the special nature of Southeast Asia Operations, a destroyer may be called on for anything from firing on targets in North Vietnam to rescuing a downed flier.

Off North Vietnam, destroyers and cruisers on Operation Sea Dragon continually patrol the coastline in search of waterborne logistics craft. And because of these patrols, the number of logistics craft sighted along the coast has been cut from an average of more that 50 a day to less than 10.

The North Vietnamese have also learned to respect the accuracy of naval guns against targets ashore. Although logistics craft are the primary targets of ships on Sea Dragon, military targets such as surface-to-air missile sites and ammunition storage areas in North Vietnam are attacked regularly by cruisers and destroyers.

A few miles farther out in the gulf, destroyers and larger frigates with a mission of "search and rescue" are on station, their crewmen, hoping their services will never be needed. When they are needed, a Navy or Air Force plane has been downed--either at sea or in North Vietnam.

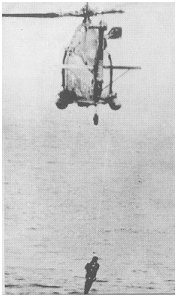

Operating from the search and rescue ships, helicopters are airborne only minutes after the ship receives a distress call, and they can reach the coast within a few more minutes. After a flier has been picked up by a helicopter, sometimes under heavy North Vietnamese gunfire, he is returned to the nearest search and rescue ship, where a Navy doctor is ready to handle almost any medical emergency.

Throughout the Tonkin Gulf, destroyers and frigates ride shotgun on Seventh Fleet aircraft carriers, protecting them from possible attack by aircraft, submarine or surface ships and standing ready to rescue pilots after landing or takeoff mishaps.

Both cruisers and destroyers have been lauded for their roles in shore bombardment and naval gunfire support. Working in all four corps areas of South Vietnam, cruisers and destroyers are continually supporting friendly troops ashore with heavy gunfire. Daily, ships on the "gun line" are credited with destroying enemy staging areas, bunkers, supply and ammunition storage areas, and even entire companies of enemy troops.

Along the length of South Vietnam's coast, radar picket escorts on Operation Market Time systematically inspect junks and sampans, helping insure that no enemy supplies are infiltrated into South Vietnam by sea.

Except for Market Time, which is handled entirely by radar picket escorts and smaller craft, a typical tour for a destroyer in the Seventh Fleet often includes time on each of these operations.

With their heavy punch, their speed and their ability to switch form task to task with apparent ease, cruisers and destroyers are ideally suited to the high tempo of operations in the Vietnam area.

OPERATION SEA DRAGON

"Patrol the North Vietnam coastline from the demilitarized zone northward and destroy North Vietnamese waterborne logistics craft carrying arms and materials to enemy troops in the South." These were the orders received by the destroyers Mansfield and Hanson on the morning of October 25, 1966, and they marked the beginning of Operation Sea Dragon. Before the day was complete, the two destroyers had destroyed several logistics craft and had been taken under fire by heavy shore batteries, returning the fire and destroying the batteries.

Although the widely-know Ho Chi Minh trail over the mountains and into the south is still a prime enemy supply route, until Operation Sea Dragon began the Tonkin Gulf was equally important to North Vietnam for moving supplies.

Since U.S. cruisers and destroyers first appeared off North Vietnam in search of logistics craft, however, the barges and junks the plied the coastline have been all but completely stopped by heavy gunfire. The craft range from 20-foot sailing junks to steel-hulled, motorized barges more than 120 feet in length, and during the first six month of Operation Sea Dragon, more than 1,000 were damaged or destroyed.

In February 1967, the scope of Sea Dragon was increased to include military targets ashore in North Vietnam. Although waterborne logistics craft remain the primary targets of ships on Sea Dragon, anything that contributes to North Vietnam's military effort is a potential target.

Targeting is normally done by the Sea Dragon commander, a rear admiral who also commands the Seventh Fleet's Cruiser-Destroyer Group. Aboard his flagship off the coast, intelligence and reconnaissance data is carefully evaluated, and the most lucrative targets are selected. Care is taken to insure that no targets are selected near populated areas and that each target has know military value.

Once targets have been approved by the Sea Dragon commander, they are assigned to ships of the task group, normally several destroyers and a cruiser.

At a pre-determined time, the ships converge on one point and approach the coast together, some firing on heavy North Vietnamese gun positions which line the coast while others attack such targets as highway choke points, surface-to-air missile sites, and petroleum oil storage areas.Overhead, spotter aircraft from Seventh Fleet carriers radio gun corrections to the ships and report when targets are destroyed.

In short, cruisers and destroyers on Operation Sea Dragon have succeeded in depriving the North Vietnamese of free use of their sea coast and coastal areas as transport routes to the south.

NAVAL GUNFIRE SUPPORT

Accuracy is the key word in naval gunfire support--accuracy that enables cruisers and destroyers to fire projectiles up to 15 miles inland at an enemy who may be within a few hundred yards of friendly forces. And that accuracy is backed by mobility unmatched by ground-based military artillery and more readily available than aircraft.

Although there are many similarities between naval gunfire support and Operation Sea Dragon, they differ in two important areas: naval gunfire support is normally fired at the request of troops ashore, while Sea Dragon's mission is the interdiction of supplies and destruction of military targets; and naval gunfire support is always conducted in South Vietnam, while Sea Dragon missions are fired only above the

demilitarized zone.

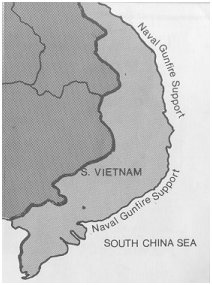

Geographically, the Republic of Vietnam is ideal for naval gunfire. The country's sprawling coastline, narrow breadth and navigable coastal waters mean that cruisers and destroyers can move in close and hit targets deep inland. The country's dependence on the sea means that many villages and towns, and as a result many of the enemy's activities, are near the coast and within easy range of naval guns.

Naval gunfire support ships have the ability to loiter in an area indefinitely or to speed along the coast at more that 30 knots. A ship assigned to gunfire support might spend her early morning hours softening up a beach before an amphibious assault, answer a call for an emergency mission against enemy troops in the afternoon, and fire illumination rounds and H and I (harassment and interdiction) fire through the night.

A gunfire mission begins with a request from a naval gunfire liaison officer ashore in South Vietnam. When a ship arrives on station, she contacts ground or airborne spotters by radio for last minute instructions.

At first the ship fires her rounds slowly and deliberately, while the spotter radios corrections. Within a few rounds, under the guidance of the spotter, the ship's projectiles find their mark and the pace of the firing quickens. The ship can remain on station until the targets are completely destroyed, and at the end of the mission hundreds of rounds may have been fired.

But one target destroyed means another to take under fire, and unless the ship is needed for another target in an area, she wastes no time in getting to another target along the coast. [Map inset: From the DMZ in the north to the Mekong Delta and beyond in the south, gunfire support ships provide mobile and responsive firepower for Allied forces ashore.]

SEARCH AND RESCUE

To Navy and Air Force pilots flying strikes against North Vietnam, destroyers and frigates on search and rescue (SAR) duty a few miles off the coast represent a real source of security. Countless times, thanks to SAR ships, downed fliers have been snatched from the sea or from North Vietnamese soil, sometimes only moments before eminent capture.

If they must ditch their planes, pilots know that if they can make it to the coast, their chances for  rescue are excellent. Helicopters operating from the SAR destroyers and frigates can cover more than a hundred mile in a hour and if a flier hits the water within sight of a friendly ship, chances are excellent that he will be aboard in less that 15 minutes.

rescue are excellent. Helicopters operating from the SAR destroyers and frigates can cover more than a hundred mile in a hour and if a flier hits the water within sight of a friendly ship, chances are excellent that he will be aboard in less that 15 minutes.

Perhaps as much as 80% of their item in the Tonkin Gulf, SAR ships steam in lazy circles. But their crewmen are always alert for a call for help, always hoping it never comes. when a call does come, however, the ships come alive with activity.

In the CIC aboard the SAR ship, information from all available sources is evaluated and the best estimate of the flier's location is passed to the bridge.

On the bridge, the location is plotted and the OOD heads the ship for the position at flank speed, while the ship's flight deck team and helicopter crew literally race through the ship to their flight quarters. Within moments the helicopter is airborne and en route to the downed flier.

If a flier is injured or cannot help himself, a helicopter crewman goes into the water, lacing the flier in a harness to be hoisted into the hovering helicopter. If there are enemy forces nearby, the helicopter's machine guns are used, while the SAR destroyer, if she is nearby, provides covering fire with her five-inch guns. Back aboard the destroyer or frigate, a Navy doctor is standing by to handle almost any medical emergency. Each sea-air rescue team had a doctor.

With one search and rescue completed, the ship returns to her station, again waiting for the inevitable call for help.

CARRIER OPERATIONS

One of the most powerful arms of the Seventh Fleet is the Attack Carrier Striking Force, which flies daily strikes against North Vietnam form three attack carriers on Yankee Station in the Tonkin Gulf. And one of the least glamorous but most necessary of all the destroyer's jobs is escorting carriers, know as plane-guarding.

During flight operations, a carrier must have a steady wind over her flight deck to launch and recover aircraft, and when there is no wind, she must maker her own by steaming on steady course. A favorite trick of some foreign trawlers is trying to force carriers off course during flight operations, delaying the launch of recovery of aircraft. But with destroyers and other ships to run interference, carriers seldom have to alter their courses for other ships.

Throughout flight operations, often more that 12 hours a day, destroyers escorting carriers have "life guard" stations manned, ready to retrieve downed fliers from the water in the event of a landing or takeoff mishap. Alert destroyermen at their lifeguard stations have saved many lives.

Destroyermen are also accustomed to escorting another kind of carrier.With maneuverability, anti-submarine weapons and powerful sonar high on their list of assets, destroyers join with anti-submarine carriers to form the Seventh Fleet's anti-submarine group. Operating both in the Tonkin Gulf and elsewhere, units of the anti-submarine group work together as a highly-skilled group of specialists, capable of detecting, localizing and destroying enemy submarines which threaten surface forces.

OPERATION MARKET TIME

The South Vietnam coastline appears today much like it did a hundred years ago. Brilliant white sand  stretches from the water's edge to a deep green treeline, with a backdrop of mist-covered mountains in the distance.

stretches from the water's edge to a deep green treeline, with a backdrop of mist-covered mountains in the distance.

The coastal waters are alive with Vietnamese watercraft--ranging from wooden junks and sampans under sail to large, steel-hulled trawlers and barges, powered my modern engines, an average of one craft for each mile of coast.

A thousand miles of coastline is a tempting invitation for the Viet Cong to smuggle men and equipment into South Vietnam, but U.S. Navy and Coast Guard forces have teamed up on an operation know as Market Time to make any Viet Cong acceptance of the invitation an expensive proposition.

Working with swift boats, harbor patrol craft, Coast guard cutters and other small craft on Market Time are the Cruiser-Destroyer Group's radar picket escorts. while the smaller craft patrol the waters nearest the coast, the radar picket escorts form the outer perimeter of the patrol area.

Working with swift boats, harbor patrol craft, Coast guard cutters and other small craft on Market Time are the Cruiser-Destroyer Group's radar picket escorts. while the smaller craft patrol the waters nearest the coast, the radar picket escorts form the outer perimeter of the patrol area.

Each Vietnamese craft along the coast must be stopped and searched to insure that no illegal cargo is smuggled into South Vietnam. Identification papers are required of each crewman and passenger, and cargo manifests must list each piece of cargo carried.

Tools used on Operation Market Time range from modern radar to old lengths of chain. the radar picket escorts use their long range radar to sweep the coastal areas and detect boats, while virtually every Navy and Coast Guard craft on Market Time uses a length of chain, passed beneath a Vietnamese boat's hull, to detect illegal cargo suspended from the hull.

But the combination of small craft and large ships, old tools and modern radar, and 24-hour-a-day perseverance on Operation Market Time has paid off. Infiltration of enemy supplies, equipment and men into South Vietnam by sea has been cut to a minimum by Market Time forces.

NAVAL GUNS

Ships operating in the Vietnam area run the gamut of naval gunnery, from the three-inch guns aboard  destroyer escorts and radar picket escorts to the massive eight-inch guns aboard heavy cruisers.

destroyer escorts and radar picket escorts to the massive eight-inch guns aboard heavy cruisers.

Most common of all guns in the Navy today are five-inch guns, which are found aboard every destroyer in the fleet. the older five-inch/38 caliber guns are the mainstay of destroyer gunnery because of their range and reliability, while modern, rapid-fire five-inch/54 caliber guns serve as main battery guns aboard newer destroyers and guided missile destroyers.

In naval gunnery, the first measurement given is the diameter of the bore and the second, if multiplied by the diameter gives the length of the bore. Thus, a five-inch/38 caliber gun has a bore five inches in diameter and (5x38) 190 inches long.

EIGHT-INCH

Eight-inch/55 caliber guns are found only aboard heavy cruisers and are used extensively on both Operation Sea Dragon and naval gunfire support. They have a range of approximently 15 nautical miles and fires projectiles weighing over 250 pounds.

SIX-INCH

Six-inch/47 caliber guns are found only aboard light cruisers. They have a range of approximately 12 nautical miles and fire projectiles weighing more than 100 pounds.

FIVE-INCH/54

Five-inch/54 caliber guns are found on post-World War II destroyers and guided missile destroyers and, because of their high rate of fire and range, are among the most versatile guns in the Navy. They can fire up to 45 rounds per minute, delivering 70-pound projectiles more than 12 nautical miles.

FIVE-INCH/38

Five-inch/38 caliber guns are carried by World War II vintage destroyers, by some destroyer escorts and, as secondary battery guns, by both heavy and light cruisers. they can fire their 55-pound projectiles more than eight nautical miles.

THREE-INCH

Three-inch/50 caliber guns are carried by most destroyer escorts and all radar picket escorts. They fire 13-pound projectiles about six nautical miles.

NAVAL GUNFIRE CONTROL

The accuracy of naval gunfire stems largely from a complex gunfire control system made up of a radar-equipped fire control director to located and track targets and a fire control computer to compensate for variables. with the position of the ship and the relative position of the target known, the fire control system aims the ship's guns so that rounds are delivered on target nearly 100% of the time.

The first step in gunfire control is to obtain an exact picture of the ship's position, which can be done by taking visual bearings on geographical points or by taking ranges and bearings of the same points with the ship's navigational radar or fire control radar. Once the ship's position has been plotted on a chart, the target is plotted, and the range and bearing determined from the ship to the target.

The first step in gunfire control is to obtain an exact picture of the ship's position, which can be done by taking visual bearings on geographical points or by taking ranges and bearings of the same points with the ship's navigational radar or fire control radar. Once the ship's position has been plotted on a chart, the target is plotted, and the range and bearing determined from the ship to the target.

With the initial range and bearing from the ship to the target fed into the computer, the computer compensates for the ship's course and speed and for other variables such as the target's course and speed (if any), wind speed and direction, air temperature, pitch and roll of the ship, and the initial velocity of the projectiles being fired. The computer's solution automatically aims and elevates the gun barrels.

With the initial range and bearing from the ship to the target fed into the computer, the computer compensates for the ship's course and speed and for other variables such as the target's course and speed (if any), wind speed and direction, air temperature, pitch and roll of the ship, and the initial velocity of the projectiles being fired. The computer's solution automatically aims and elevates the gun barrels.

Navy ships are capable of placing their first rounds within a few hundred feet of their target. In addition, whenever possible, Navy and Air Force aircraft or ground spotters assist the ships by spotting or locating the fall of shot in relation to the target. With spotters passing corrections to the firing ship, projectiles can literally be "talked" or "walked" to the center of a target in a matter of minutes [Photo: From high up on the ship's superstructure, the radar-equipped director feeds target information to the ship's computer deep inside.]

REPLENISHMENT AT SEA

To the casual observer, and even to the seasoned yachtsman, the sight of two large ships lumbering along at 15kts less than 100 feet apart might seem disconcerting, but it is the cornerstone of one of the most common of all Navy evolutions, the underway replenishment.

"The USS Mattaponi AO-41 made seven deployments to Vietnam waters during and before the war started. Our deployment schedule largely coincides with the USS Mansfield DD 728. Possibly, Sea Dragon readers might be interested in what was going on. Our unrep (underway replenishment) and inrep (inland replenishment) schedules and logistic maps, as plublished in our ship's newsletter "ON STATION", gives us a snap shot, showing where all the players are at in a specific time in history." -- Dennis C. Miller SH2, USS Mattaponi 1966-70. Go here for maps showing a sampling of the Mattaponi's role in the Vietnam War.

"The USS Mattaponi AO-41 made seven deployments to Vietnam waters during and before the war started. Our deployment schedule largely coincides with the USS Mansfield DD 728. Possibly, Sea Dragon readers might be interested in what was going on. Our unrep (underway replenishment) and inrep (inland replenishment) schedules and logistic maps, as plublished in our ship's newsletter "ON STATION", gives us a snap shot, showing where all the players are at in a specific time in history." -- Dennis C. Miller SH2, USS Mattaponi 1966-70. Go here for maps showing a sampling of the Mattaponi's role in the Vietnam War.

Although her assets more that balance the scale, one of a destroyer's critical restrictions is her limited capacity for fuel, ammunition, food and other stores. To preclude here having to return to port for fuel and supplies every few days, she depends on oilers, ammunition ships and stores ships to replenish her while on station in the Tonkin Gulf of South China Sea.

Most cruisers and destroyers in the Vietnam area have large underway replenishments at least twice a week, often taking on more than 100,000 gallons of fuel, 1,000 rounds of ammunition, several tons of fresh food and other supplies and sometimes mail from home.

During a replenishment, a cruiser or destroyer might be alongside an ammunition ship for as long as two hours, connected by lines and cables hauling ammunition across a hundred feet of swirling white water.

During a replenishment, a cruiser or destroyer might be alongside an ammunition ship for as long as two hours, connected by lines and cables hauling ammunition across a hundred feet of swirling white water.

With dusk approaching and the ammunition transfer complete, the destroyer leaves the ammunition ship and another pulls up to take her place. The first destroyer steams to a station a few miles away, moving into position to take a long, thirsty drink of fuel oil. As dusk slips into evening, daylight is replaced by red lights, casting an eerie glow over the mammoth oiler and the destroyer beside her.

The replenishment completed, the cruisers and destroyers return to their duties, and the replenishment ships steam up the coast to another rendezvous. And another.

SHIPS OF THE GROUP

Heavy Cruiser

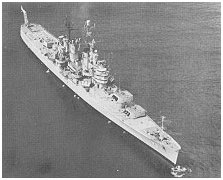

Heavy cruisers in the Vietnam area are used primarily on Operation Sea Dragon, naval gunfire support and in support of amphibious landings, because of their heavy firepower. Carrying both eight-inch and five-inch guns, these ships can hit targets up to 15 nautical miles away with their main batteries while concentrating on enemy guns along the coast with their secondary batteries.

Heavy cruisers in the Vietnam area are used primarily on Operation Sea Dragon, naval gunfire support and in support of amphibious landings, because of their heavy firepower. Carrying both eight-inch and five-inch guns, these ships can hit targets up to 15 nautical miles away with their main batteries while concentrating on enemy guns along the coast with their secondary batteries.

Light Cruiser

Light cruisers in the Vietnam area are used primarily on naval gunfire support, operation Sea Dragon, and in support of amphibious landings. They carry six-inch guns with a range of 12 miles and five-inch guns with a range of seven miles. In addition, they are equipped with supersonic surface-to-air missiles.

Light cruisers in the Vietnam area are used primarily on naval gunfire support, operation Sea Dragon, and in support of amphibious landings. They carry six-inch guns with a range of 12 miles and five-inch guns with a range of seven miles. In addition, they are equipped with supersonic surface-to-air missiles.

Guided Missile Frigate

Guided missile frigates have many jobs in the Vietnam area, including sea-air rescue duty, carrier operations and , because of their sophisticated combat information centers, serving as aircraft control and tracking stations in the Tonkin Gulf. with their supersonic missiles, frigates provide excellent protection of carriers and other ships from hostile aircraft attack.

Guided missile frigates have many jobs in the Vietnam area, including sea-air rescue duty, carrier operations and , because of their sophisticated combat information centers, serving as aircraft control and tracking stations in the Tonkin Gulf. with their supersonic missiles, frigates provide excellent protection of carriers and other ships from hostile aircraft attack.

Guided Missile Destroyer

Guided missile destroyers are among the most versatile ships in the Navy, and they can be used for many jobs in the Tonkin Gulf and South China Sea. In addition to surface-to-air missiles, they carry rapid-fire five-inch/54 caliber guns and excellent sonar systems, and they are used extensively on naval gunfire support, Operation Sea Dragon, carrier operations and anti-submarine patrols.

Guided missile destroyers are among the most versatile ships in the Navy, and they can be used for many jobs in the Tonkin Gulf and South China Sea. In addition to surface-to-air missiles, they carry rapid-fire five-inch/54 caliber guns and excellent sonar systems, and they are used extensively on naval gunfire support, Operation Sea Dragon, carrier operations and anti-submarine patrols.

Destroyer

Destroyers of the World War II vintage in the Vietnam area, all of which have received extensive rehabilitation and modernization, are well suited for a wide variety of operations. Their five-inch/38 caliber guns are used daily on Operation Sea Dragon and naval gunfire support, while their speed and maneuverability are used to advantage on search and rescue duty and carrier operations. These ships are the backbone of today's destroyer forces.

Destroyers of the World War II vintage in the Vietnam area, all of which have received extensive rehabilitation and modernization, are well suited for a wide variety of operations. Their five-inch/38 caliber guns are used daily on Operation Sea Dragon and naval gunfire support, while their speed and maneuverability are used to advantage on search and rescue duty and carrier operations. These ships are the backbone of today's destroyer forces.

Destroyers of the Forrest Sherman and Hull classes are the newest destroyers in the Navy and are similar to the guided missile destroyers in their hull design, gunnery and sonar. They are used extensively on Operation Sea Dragon and naval gunfire support because of their capable five-inch/54 guns and on anti-submarine patrols because of their excellent sonar systems.

Destroyers of the Forrest Sherman and Hull classes are the newest destroyers in the Navy and are similar to the guided missile destroyers in their hull design, gunnery and sonar. They are used extensively on Operation Sea Dragon and naval gunfire support because of their capable five-inch/54 guns and on anti-submarine patrols because of their excellent sonar systems.

Destroyer Escort

Fast destroyer escorts of the Garcia class are used primarily on anti-submarine patrols and carrier operations because of their excellent sonar systems and anti-aircraft batteries. In Addition, they require less fuel than larger ships, making possible longer patrols without refueling.

Radar Picket Escort

Sometimes remaining at sea as much as 90% of their time in the Western Pacific, radar picket escorts are assigned exclusively to Operation Market Time along the coast of South Vietnam. their long endurance without refueling and the four-mile range of their guns make radar picket escorts ideal for long Market Time patrols.

Sometimes remaining at sea as much as 90% of their time in the Western Pacific, radar picket escorts are assigned exclusively to Operation Market Time along the coast of South Vietnam. their long endurance without refueling and the four-mile range of their guns make radar picket escorts ideal for long Market Time patrols.